My Most Memorable Astro-Observations

I've been an amateur astronomer for over 50 years. In that time I've had a lot of fun out under the stars, staring at the endless craters visible on the moon, straining to see the smallest details on planets, and marveling at the beauty of the numerous star objects within reach of even my small telescopes. All of it has been fun. Well almost all.

There were quite a few evenings when either the clouds or the cold ruined the evening. And there were times, back when I found targets using the old Star Hopping method, that I simply couldn't find my target. There were a few other times when I found the target, but after hunting for it for an hour or more.

Star Hopping, if you are unfamiliar with it, it is the procedure of using star charts, identifying a few naked eye or at least finder viewable guide stars, and trying to move the telescope to some non-visible sky area to locate an object too dim to see by naked eye or finder. It's a tedious procedure, especially if hunting for a target you've never seen before. You find that when you try to locate a guide star in the finder, there are many more stars than you expected to see in the view. Then when trying to hop from one guide star to another, movement distances through the finder are hard to estimate. Anyway, until you've viewed a difficult item a few times, it's often hard to find some targets with Star Hopping. Even when it's not too difficult a thing to do, it's time consuming.

But throughout all of those fun times when I could find what I wanted, and when the weather didn't do me in, there were just a few views that I recall even though in some cases decades have gone by. I'm sure, if you haven't already, you'll experience some of these special moments if you keep observing. Here are a few memories I have of special moments when observing.

It Began With My First Moderate Sized Telescope

Clear back in the 60s when I was still in high school, I had an exceptional night of observing Jupiter. I was using a 6 inch f/12 Newtonian, purchased by my small town school and loaned to me (the only student interested in astronomy). The telescope came as something less than a kit, a box of parts and a tube for the telescope. I managed to get the help of a fellow student to put the telescope parts together into a functioning telescope.

Once the telescope was assembled, I cobbled together a Turn on Threads

type of pipe fitting mount, not terribly different than the one I use now:

The Pipe Fitting Mount shown here is hosting a small refractor, but the one I built years about was able to handle the 6 inch reflector.

How?

Basically the old one I made back then was different than my current one in two ways. Since it hosted a long reflector instead of small refractors, it was much shorter. With a refractor the eyepiece being at the bottom end when looking up, necessitates the tripod being taller.

The much lower design of the old one made it very stable. Plus, instead of just an elbow on top of the vertical axis providing the

threads for the vertical axis, a T

was used, so that one side had the polished threads for the vertical axis, and the opposing side of the tee just supported about an 18 inch long pipe with a counterweight on it. Below both are illustrated:

This telescope was my first serious instrument, and I learned a lot using it. I was awed by how star objects looked in it, and completely blown away by the moon views it provided. Using this telescope taught me also how frustrating Star Hopping can be. Of course the narrow field of view the f/12 instrument provided probably didn't help.

Jupiter's Festoons

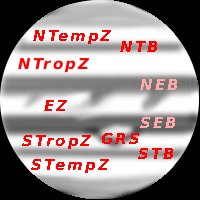

The drawing above illustrates some of the features observable on Jupiter. Among all the things I saw with that telescope all those years ago was an exceptionally clear view of Jupiter one evening. While Jupiter generally revealed plenty of detail with the Great Red Spot and the equatorial bands with their occasional dark spots, it was a view of some Festoons drooping from the edge of the Equatorial Region of Jupiter. In the illustration above, the drooping features between the NEB and the SEB are called Festoons. I'd read about them before, and of reports of other amateur astronomers seeing them (with larger instruments), but this was my first and only view of them with one of my own telescopes. A view that stays with me still.

High Flying Goose

That's right, I once saw a high flying goose flap it's way through my field of view. I was actually looking at the moon at low power, and this silhouette of a goose, just recognizable, moved across the moon. It was a one an only event I imagine, though not a purely astronomical one. An event that was unique enough that I've never forgotten it.

Airliner Back-lit by the Moon

This experience was similar to the goose viewing, but it was an airliner instead. Again it was just a silhouette back-lit by the moon, and not a very large object, perhaps twice the apparent size of Clavius Crater. But it was again an unusual event, though that event has occurred to others. I've even seen in the last few years a photograph of an airliner crossing the face of the moon.

Ganymede Transit

Much more recently, perhaps 20 years ago or so, I was out viewing with a 6 inch f/5 Newtonian. I still have that telescope, shown in a photograph below:

If you've observed Jupiter much at all, you've likely watched a few moon transits. That's where one of the Galilean Moons passes across the face of Jupiter. From the Moons of Jupiter Wikipedia page you can find the orbital periods of the Galilean moons. They are indicated in the following table.

| Moon | Period Days |

| Io | 1.8 |

| Europa | 3.6 |

| Ganymede | 7.2 |

| Callisto | 16.8 |

You can see there are some moon transits of Jupiter nearly every day. However, those transits may not occur during your observing time.

The Galilean moons are small, not really resolvable with typical amateur instruments. They can be seen for sure, just not resolved in any detail way. Even a pair of binoculars will reveal Jupiter's moons, looking like pin points of light stretched across a nearly straight line to either side of the much brighter image of Jupiter

The moons are also fairly light colored. So when a moon crosses over the face of Jupiter, it is usually invisible to any typical amateur sized telescope, given that they usually pass near the equatorial region of Jupiter, which is also light colored. That's not at all true, however, for the shadows the moons cast onto the upper clouds of Jupiter.

These shadows are stark black spots easily seen on the surface with even a 60mm telescope. Below is an early effort of mine to capture a transit of Io with my little ETX 90 telescope. I hadn't developed much of a technique back then, but at least these somewhat crude images show that a small telescope (ETX 90) can in fact see transits of moons on Jupiter.

What the series of photos show is the shadow of Io (the darkest spot in each image) as it traversed the face of Jupiter. The photos were taken several minutes apart.

But! On one fateful evening some years ago, apparently a strange weather phenomenon gave me a much clearer image, which I observed by the aforementioned 6 inch f/5 Newtonian. That day had been cool and very cloudy. But in the evening the clouds rolled away, and it the temperature dropped 20 to 30 degrees. That cool night air gave me one of the best views of Jupiter I've ever had.

There was another element to the weather, however. There was still moisture in the air from the front that had moved through. The telescope has a metal (think stove pipe) tube. That tube became very cold, and the moist air touching it caused a lot of dew to accumulate. Fortunately, with a Newtonian the mirrors are fairly safely mounted within the tube, so they didn't experience any dew.

The final special part of that nearly perfect seeing condition evening was that Ganymede was transiting Jupiter. But being a bit further out in it's orbit, the latitude range of its transits varies more than those of Io and Europa. In this case, Ganymede was crossing not across the light colored equatorial region of Jupiter, but across the bottom edge of the north polar region of Jupiter. This was advantageous because that region is darker than the equatorial region. In this special case, Ganymede, being fairly light colored, was visible as it crossed the darker background. So I observed on this occasion not the shadow of Ganymede as it rode across the upper clouds of Jupiter, but the actual moon of Ganymede itself.

Lunar Eclipse

As the image above shows, a lunar eclipse is when the moon gets eclipsed by the earth. The moon ends up in the earths shadow, and at totality takes on a red-orange hue, as shown in the MicroObservatory photo below. The image below is of a lunar eclipse that took place in 2021. If you look up other photos of that eclipse, you'll see the red-orange color. In the photo below, I had to add false color because the MicroObservatory only offers black and white photos of the moon. The low contrast of the lunar features are cause by the moon being in earth's shadow.

The red color is caused by the filtration of the light as it passes through the earth's atmosphere and is diffracted to illuminate the moon. Only the red light makes it through the atmosphere.

But on my most memorable eclipse that occurred a couple of decades before 2021, I watched intently the early stages of the eclipse, and it's those views that impressed me. I was using the f/5 Newtonian on that occasion also, and I was watching the moon as the earth's shadow move along covering the moon. The edge of the earth's shadow is what I noticed most.

While most of the shadow was initially just a normal darkening, right at the edge of the shadow the view was different. That's because the very edge of the earth's shadow showed the absorption aspects of the earth's atmosphere. A band that looked to be perhaps 20 miles wide was leading the shadow across the moon. This band had the most intriguing, blue-slate color. I followed that band all across the moon, and as totality approached, so did the red-orange color of the shadow trailing the blue-slate edge.

I've not taken the time to view another eclipse so intently, so I've not watched that effect again. But I'll never forget that view. Look for it on your next lunar eclipse opportunity.

Summary

There's really nothing particularly special about my re-callable observing moments. They are just special to me because for some reason they've planted themselves into my memory. But hopefully knowing what modest instruments I was using to have these moments will inspire you to observer more yourself. And I'm sure in a few months or years, you'll have some memorable viewing events too, if you haven't already.

No comments:

Post a Comment